I walked into the King’s Head pub and knew I was working with two, equally powerful, people – Joan and Dan Crawford. It was 1971, just one year after this imaginative couple created the upstart, cheeky theatre venue. Directors, actors, stage-managers working at the King’s Head Theatre accepted that they had to satisfy two bosses. Yet, over the years, the surviving big gun – and not for the first time in history – massaged the truth to make us, the world, believe that the marvellous invention was entirely his own, unassisted creation, inspiration. His wife’s role was written out, nixed, obliterated.

The King’s Head, Islington. The most famous pub theatre in the world. How it was REALLY founded; introducing Joan Crawford. Joan’s remarkable story is here:

Here’s to the King’s Head Theatre by Joan Crawford: Part one

The King’s what??? This is the response actors’ and writers’ agents used to give 35 years ago when approached by what is now hailed as Britain’s leading fringe theatre. This is one of a thousand memories that assailed me when I read the sad news of Dan Crawford’s death. Dan and I started the Kings Head pub theatre together in 1970. It is a wild, wonderful and hugely improbable tale which seems at this point to be well worth the telling. To begin with, neither of us had ever managed a pub, or run a theatre — Dan had worked as barman and stage manager, I had worked as a waitress and had done some acting at University. Hardly impressive credentials.

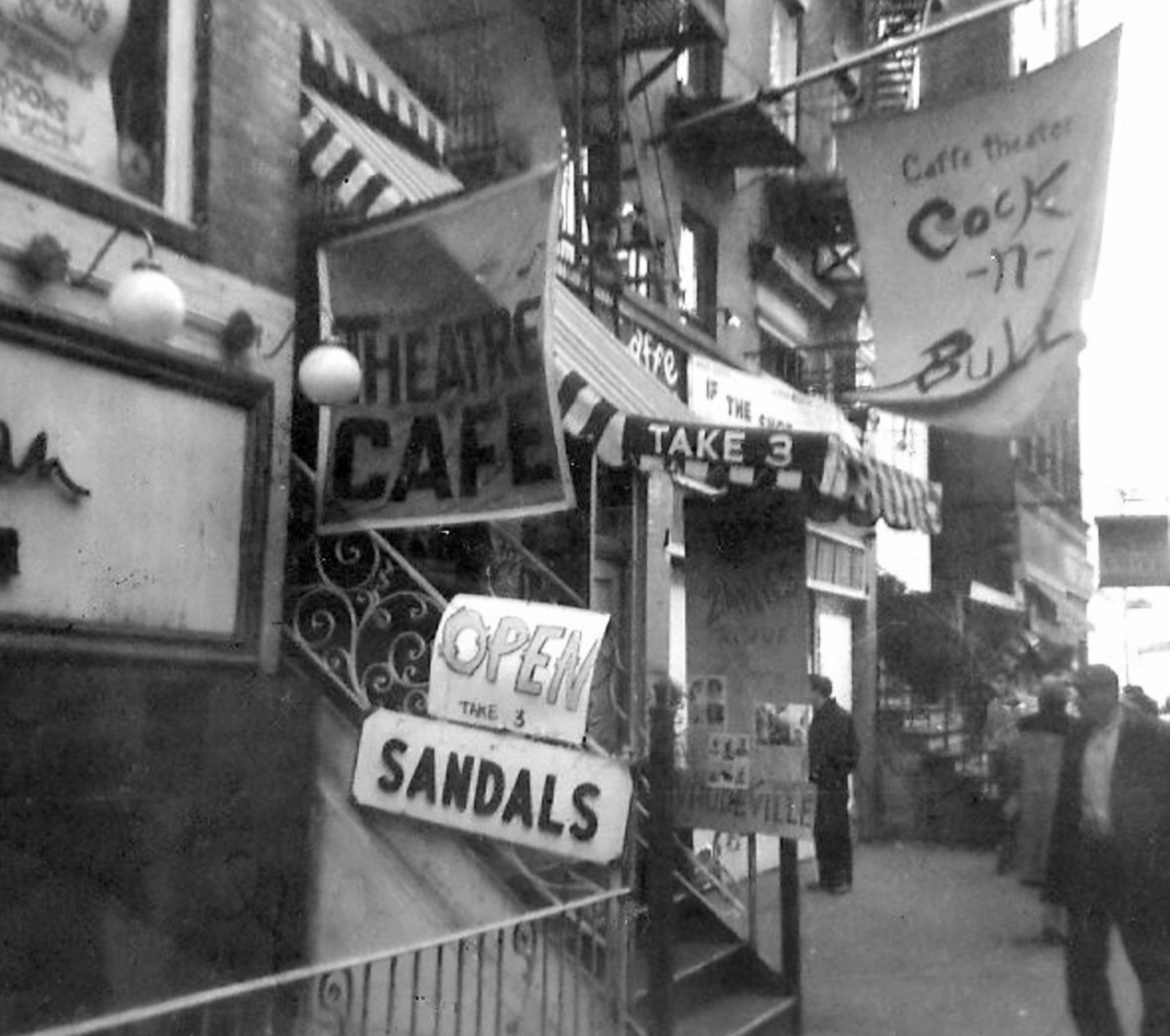

When I first met Dan he was looking for a pub to run as a Greenwich Village type bar. One evening, over several glasses of wine, he said: “Maybe it could have a dinner theatre as well”. At that moment the mutual dream was born. Dan had a small amount of capital and I had none. Also, as a Canadian and an American, we knew nothing about the London theatre scene. However, in our total naivete, enthusiasm and innocence we were not in the least deterred.

We decided to explore an affordable up and coming area and settled on Islington. Upper Street seemed the best bet. One spring evening we started at the bottom of the main drag, stopping at any pub that looked even remotely possible, ordered a glass of wine, and at some point innocently said to a member of the bar staff, ‘I understand that this pub is for sale’. We were greeted with bemusement until, half way up Upper Street, already well oiled, we entered the gloom of The Kings Head. It was virtually empty. I asked for a glass of red wine and, such a request being entirely unfamiliar, was given port. When we recited our well rehearsed line, the barman said, ‘Yes, it’s been on the market for months. It’s a total white elephant and nobody wants to buy it.’

The clubroom in the back had been variously used as a boxing ring and a folk club venue, and seemed the ideal space for the theatre we had envisioned.When we approached the brewery area manager, he was clearly desperate to offload this pub but our proposal met his, entirely understandable, scepticism. What swung it was that his superior, the regional manager, had a passion for amateur dramatics and was swept along by our enthusiasm. With £1100 to purchase the so-called furniture and the stock on hand, we became the proud and terrified tenants of the Kings Head in July 1970.

Over the next five months, with the help of many willing hands, we redecorated the pub and fitted out the theatre: sanded floors, bought antiquated stage lamps from a West End theatre, picked up cast-off cinema seats, converted sewing machine bases into bar tables, built a lighting board from an antediluvian system we got for pennies. Two Canadian folk singers, Jesse and Luke, came and lived with us above the pub, helped with the conversions and in the evenings played banjo and guitar in the bar. They were a hit- the weekly turnover soared from £65 to £1000 within three months. A local Irish builder, John Scully, one of the few original regulars, passed us his business card at the bar one evening. He was rapidly converted to the cause and became foreman of the operation, working unimaginable overtime. Further funds we had expected failed to materialize, and the entire fitting – out was financed by the simple expedient of not paying our brewery bills. By the time this came to the notice of someone in accounts, the unpaid bill stood at £2000 – a lot of money in 1970. The sceptical area manager was, unsurprisingly, alarmed.

Green and broke though we were, we were approached by hungry directors and writers who had sniffed us out, eager for a platform for their work, When we opened the theatre in December 1970 with Boris Vian’s The Empire Builders, we expected droves of critics and public to come flocking through our doors. As it was, seven people straggled in for the opening night. A desultory attendance and no critical acclaim continued for the four week run. The bills got bigger and bigger. The tide turned with an adaptation of John Fowles’ The Collector. This, however, was not without a hiccup, as two weeks into rehearsal we discovered that John Fowles had not approved the adaptation, and we made a frantic visit to Lyme Regis to persuade him to let the production go ahead. When the play finally opened the stampede occurred. It met with critical acclaim and we had to hire more bar staff. We even managed to pay the brewery a portion of what we owed them. At one point someone commented to Dan that we must be rolling in it, to which he quipped, “It’s been a long hard climb from rags to rags.”