There is an entry, in the category of counts – of whom there are many – in a schedule of the Hungarian aristocracy as follows:

“Wenckheim: Article 73 of 1790/91. Austrian baron: 1776; Austrian count: 1802. The Wenckheims’ hereditary seat at the Upper House of the Diet of Hungary was confirmed by Act VIII of 1886.”

I’ve no means of verifying if this is my count’s family, but it’s not unlikely.

There is also a tantalising description of a noble des-res as follows:

“The Wenckheim Palace (pictured) was built in 1887, by Count Frigyes Wenckheim, in a neo-baroque style with neo-renaissance elements. Wenckheim, who was a wealthy aristocrat, built the palace in order to have a place to stay in when the family visited Budapest. During his visits, he hosted several charity events in the palace with his wife. After their death the city bought the building. Since 1931 it functions as one of Budapest’s largest libraries. The most grandiose ballroom has a pompous chandelier hanging from the high ceiling and elegant decoration of gold motifs on the white walls. In another room there are huge mirrors among the grand windows. There is a beautiful wood panelled library room, at least a hundred years old, with two well-furnished wooden spiral staircases. Another room has a real historic European feel with its stylish red and white striped wallpaper and gold ornamentation. There is a monumental staircase leading to these rooms from the large wrought iron gates at the entrance.”

The Wenckheim I knew was deliberately vague about describing, precisely, the family’s assets in town or country – partly from aristocratic good taste – but also so as to insist on historic rights, rather than gloat on heaps of, perhaps, unfairly acquired loot.

Astonishingly, the above is the opening paragraph you’ll see if you follow this link. It takes you to Top Filming Locations in Hungary. And the first image is of a Wenckheim palace.

Lots of significant show-biz events and stars have strutted stuff at this location. If it belonged to the Nicholas Wenckheim I knew, he would have relished the irony – given his own feverish attempts to make his name as a dramatist – and with relaxed, sardonic hatred, would have shrugged – and offered us a sweetly bitter smile.

There are also these works credited to him:

The Saga of Raoul Wallenberg: Nicholas Wenckheim’s Image and Likeness

Twelve Hundred Hostages: A Play In Seven Scenes

by Nicholas Wenckheim About American hostages in Vietnam.

Given their subject matter, they must be by the count I knew, and they tie in with his almost frantic attempts to get his work out there in the world and his deep longing to set the political record straight. But, they now seem to be in archives available to scholars and are not, currently, in general readers’ hands.

Although, there is this:

Image and Likeness

Author(s): Nicholas Wenckheim

Images and Likeness, a three act, 84 scene play that employs actors in multiple roles and masks, tells the story of Raoul Wallenberg, a Hungarian diplomat who attempted to save Jews during the Nazi occupation. Act I chronicles Holocaust life in Hungary. Act II focuses on Wallenberg’s heroic actions until the arrival of the Soviets. Act III dramatizes Wallenberg being imprisoned by the Soviets and the thirty year attempt to explain his disappearance.

Format: Historical drama

Snapshot

Notes:

For additional reading, see Gene A. Plunka Staging Holocaust Resistance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, pp. 165–186.

Original or Prominent Production: Staged as The Wallenberg Mission, Harold Clurman Theatre, New York, September 1995

Nationality of Author: Hungarian

Original Language: Hungarian

English Language Translator: Wanda Grabia

Publisher:

Exposition Press; 1st edition, 1979 (out of print)

So, an original drama of his was produced, but was it after his death?

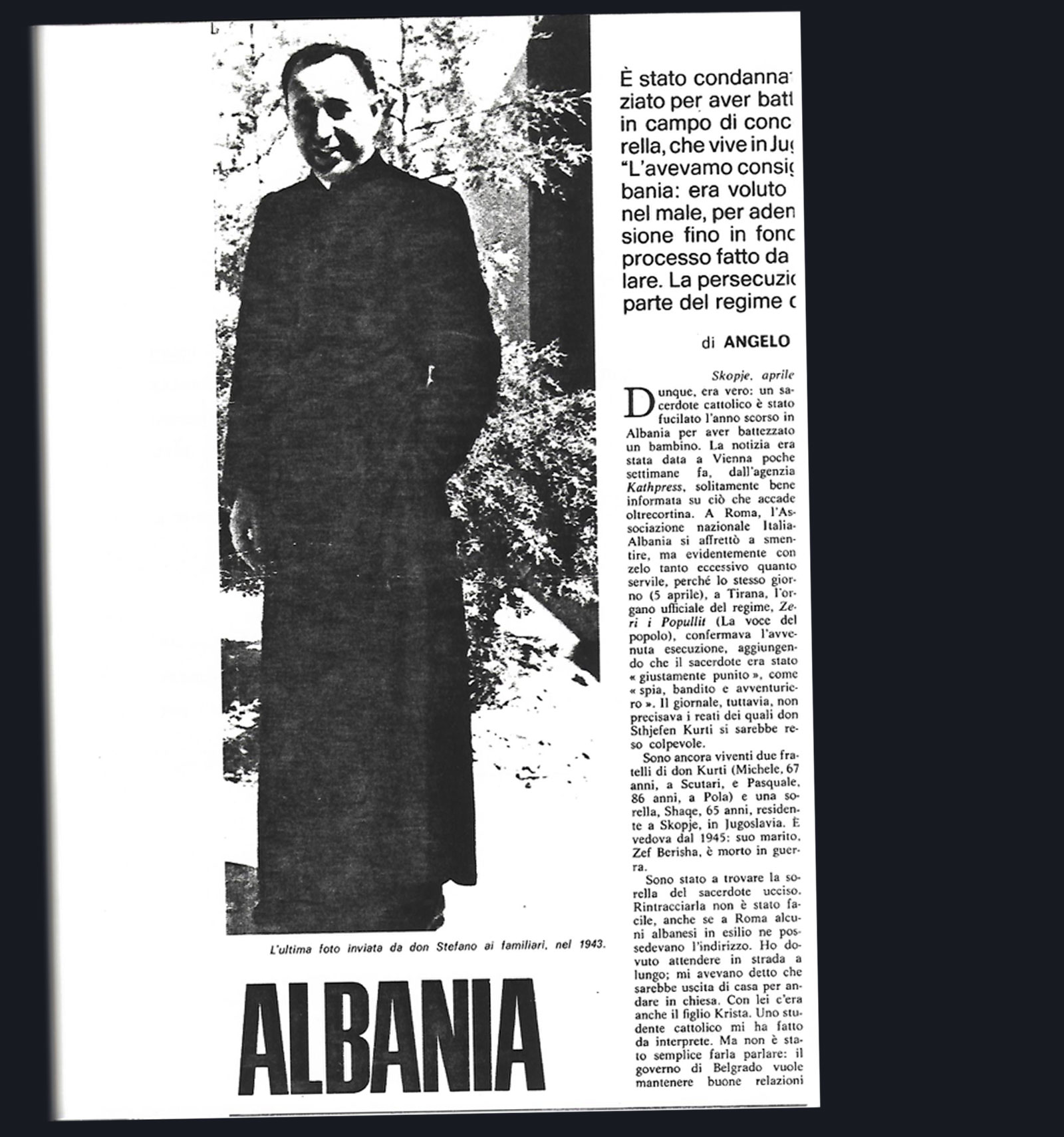

Image and Likeness is a religious concept and I still have a play of his entitled Kurti which is Nicholas’ homage to a real man. Stephan Kurti was a Catholic priest who, when in prison himself (according to Wenckheim’s version) was approached by a woman who’d given birth in the same gaol. He agrees to baptise the child, is discovered and shot. This actually happened.

Wenckheim’s play – in the ‘foreigner’s’ English that was handed to me – shows the state of morbid suspicion and lack of trust that arises in a special Soviet facility devoted to creating and training terrorists, useful to the regime. The irritant in the oyster shell arises because it emerges that the young karate expert appears to have been baptised as a new-born. In fact, he was the baby born in prison many years ago. In a succession of super-paranoid scenes, the baptised lad begins to see visions of Stefan Kurti – the real, executed priest. By a process available only to ‘believers’, the two formerly antagonistic trainee thugs, kill their Soviet handler and face certain death, wrapped in a holy glow, both able to see a vision of the dead priest, Stefan, looming up and hovering over them. It’s a miracle in a death cell; redemption, salvation… martyrdom, echoing the martyrdom of Kurti himself.

Safe to say, I think, that Nicholas was Catholic.

The play is, unfortunately, badly written (perhaps it worked in Spanish) but the underlying comprehension of how evil works is genuine.

Wenckheim doggedly binds into his text a copy of the article below, seeking to justify his thesis with external evidence – as ever.

I’ve also come across what seems to be a picaresque novel using the same name – Nicholas Wenckheim – to describe, I quote: “…the return of a disgraced aristocrat, the Baron, to his dreary hometown in Hungary after being driven out of Buenos Aires by gambling debts.”

The book is called Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming and it’s by László Krasznahorkai and this is what one reviewer says about the book:

“The playful, pessimistic fictions of the Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai emit a recognizably entropic music. His novels—equal parts artful attenuation and digressive deluge—suggest a Beckettian impulse overwhelmed by obsessive proclivities. The epic length of a Krasznahorkai sentence slowly erodes its own reality, clause by scouring clause, until at last it releases the terrible darkness harbored at its core. Many of his literary signatures—compulsive monologue, apocalyptic egress, terminal gloom—are recognizably Late Modern. But the extravagant disintegration and sly mischief of the work make him difficult to mistake for anyone else. There are the sudden, demonic accelerations; the extraordinary leaps in intensity; the gorgeous derangements of consciousness; the muddy villages of Mitteleuropa; the abyssal laughter; the pervasive sense of a choleric god waiting patiently just offstage. Here is fiction that collapses into minute strangeness and explodes into vast cosmology.”

It’s safe to say that this has nothing whatever to do with the real Wenckheim that I corresponded with – and met.

End Part Eight