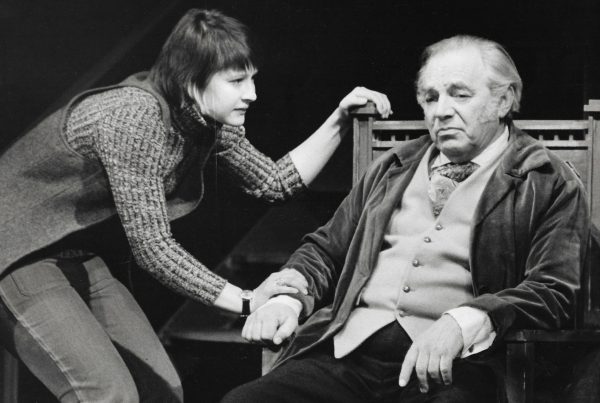

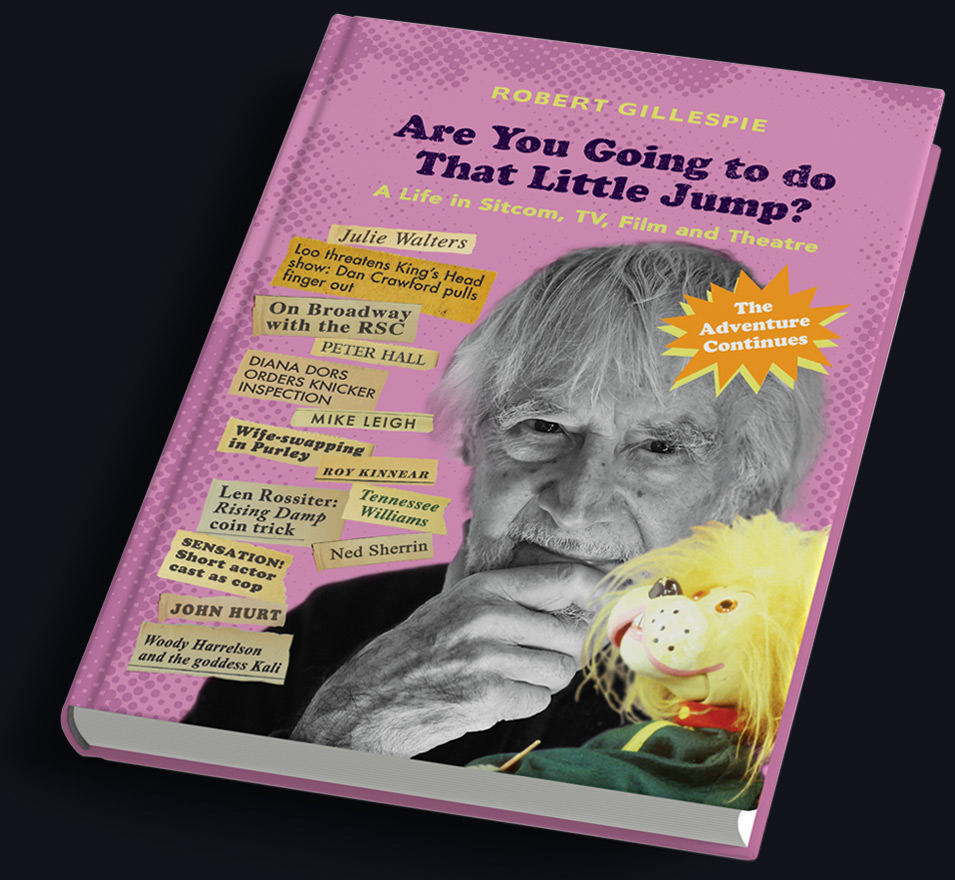

My main concern, vis-à-vis the Wrangel play, was its historical accuracy. If I were to push it at Dan and Joan Crawford at the King’s Head for production it had to be believable. On the same theme, this is the moment to say something about Raoul Wallenberg (pictured above).

He is a legend

Raoul Gustaf Wallenberg was a Swedish architect, businessman, diplomat and humanitarian. Celebrated – almost to the point of sainthood – for saving thousands of Jews in German-occupied Hungary during the later stages of World War 2. He rescued them, ingeniously, from German Nazis and Hungarian Fascists. Serving as Sweden’s special envoy in Budapest, between July and December 1944, Wallenberg issued protective passports and sheltered Jews in buildings designated as Swedish territory.

Hungary participated in the German invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941 and joined the war against the Soviet Union after the bombing of Kassa in late June. Then, fearing the defection of Hungary from the war, the Germans occupied the country on 19 March 1944.

Before that, Jews in Hungary had been tolerated. In Are You Going to do That Little Jump – The Adventure Continues I write about my Hungarian friend Andrea. “Because she was very blonde, it was she, the innocuous fourteen-year-old, who was sent out to find food by the other Jews hiding in Budapest, once the Germans there got nasty in 1944-5.”

Hundreds of thousands of Jews and tens of thousands of Romani were transferred to Nazi concentration camps with the local authorities’ assistance. The wealthiest business magnates were forced to hand over their companies and banks to redeem their own and their relatives’ lives. (This is, possibly, when Wenckheim’s fury begins.)

Then, on January 17th 1945, following the Siege of Budapest by the Red Army, Wallenberg was detained by SMERSH on suspicion of espionage and subsequently disappeared. He was later reported to have died on July 17th 1947 while imprisoned in the Lubyanka, the prison at the headquarters of the KGB secret police in Moscow. The motives behind Wallenberg’s arrest and imprisonment by the Soviet government, along with questions surrounding the circumstances of his death are obscure, debated and contested.

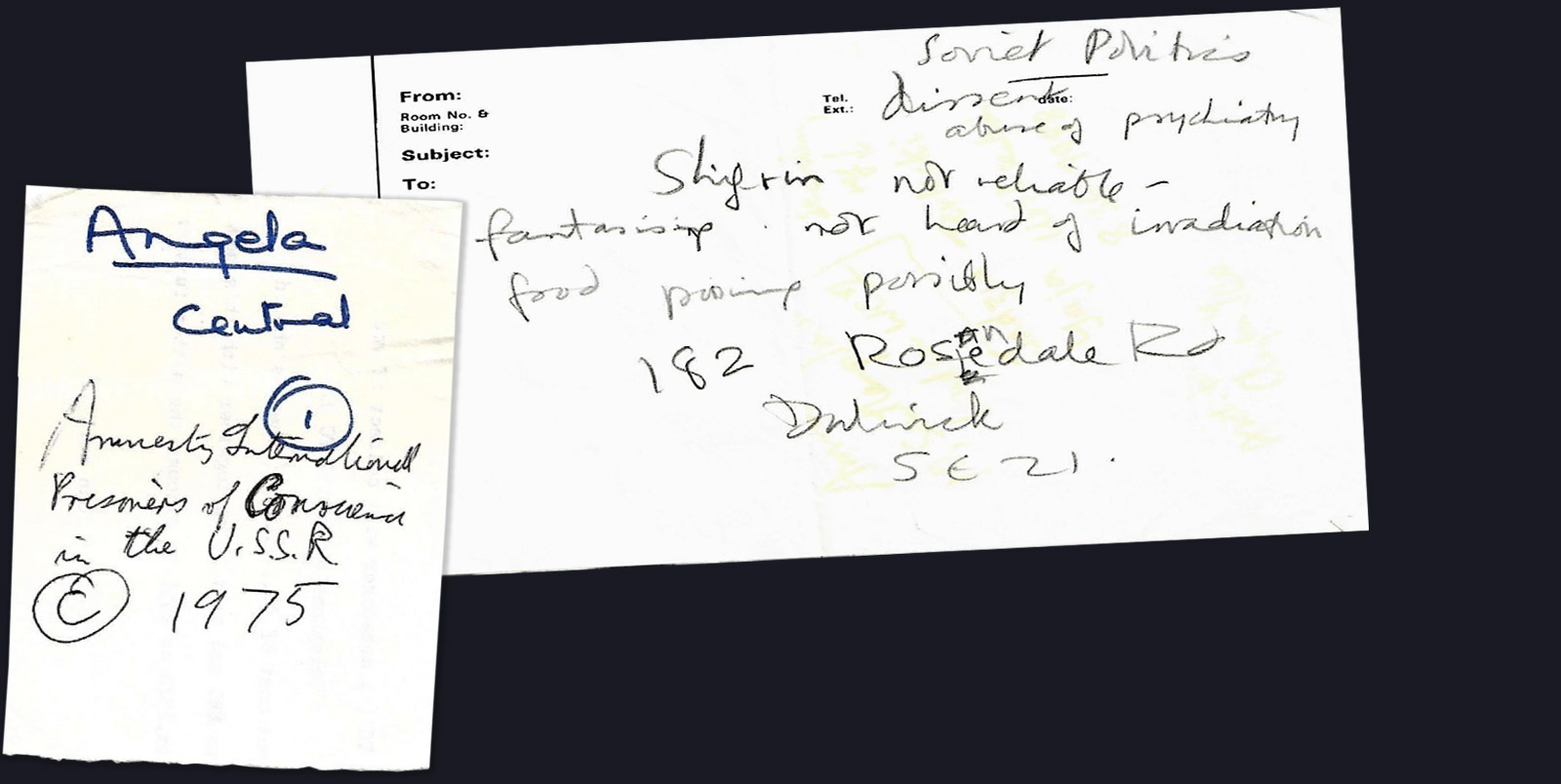

And, you will note from the Shifrin report, that many prisoners reported seeing him on Wrangel Island. Wenckheim, clearly, wanted to believe this.

Amongst other things, this was our response to Nicholas’ Wallenberg (click to enlarge).

And this is the New Scientist article. It tells what the CIA – the US – was up to.

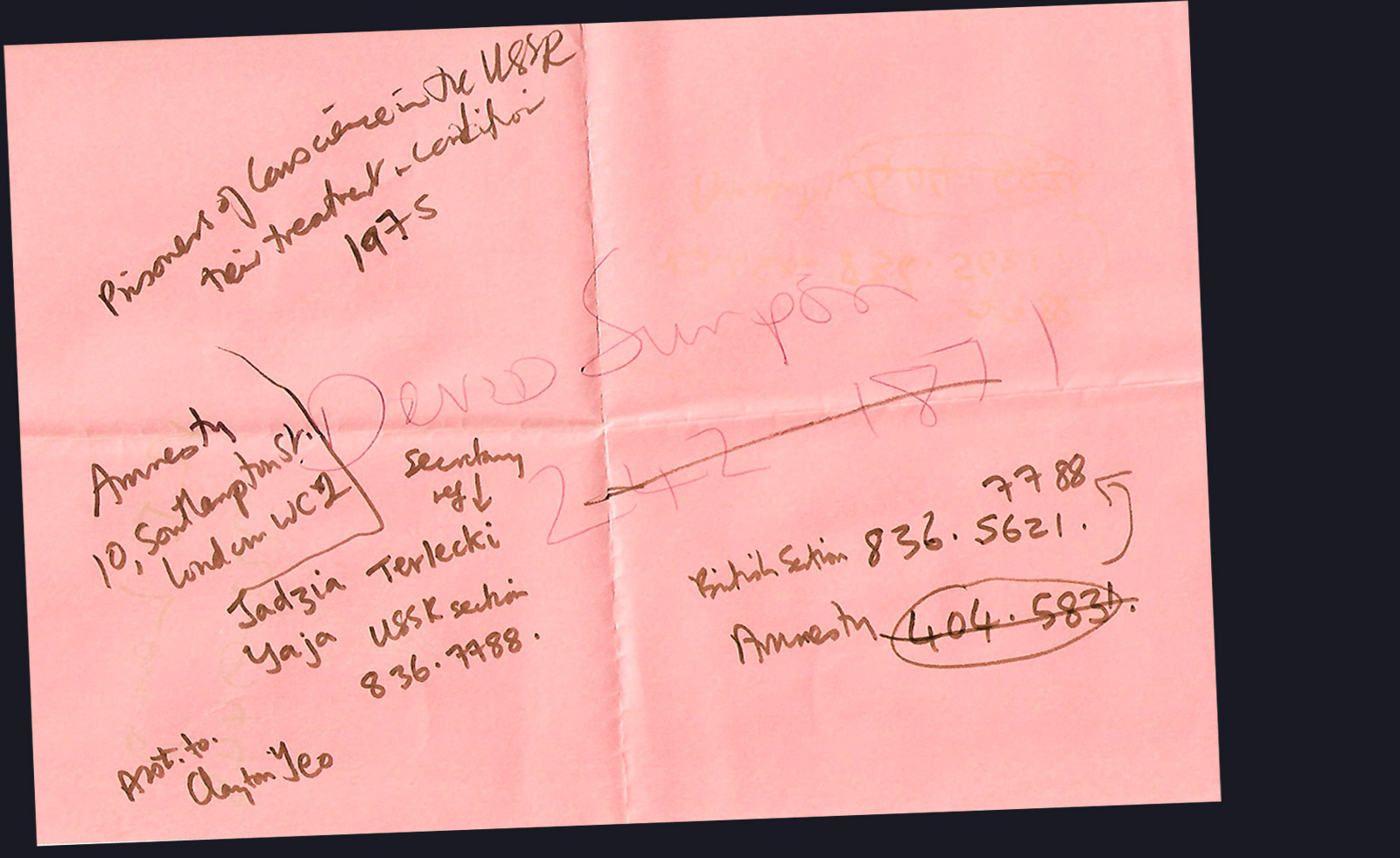

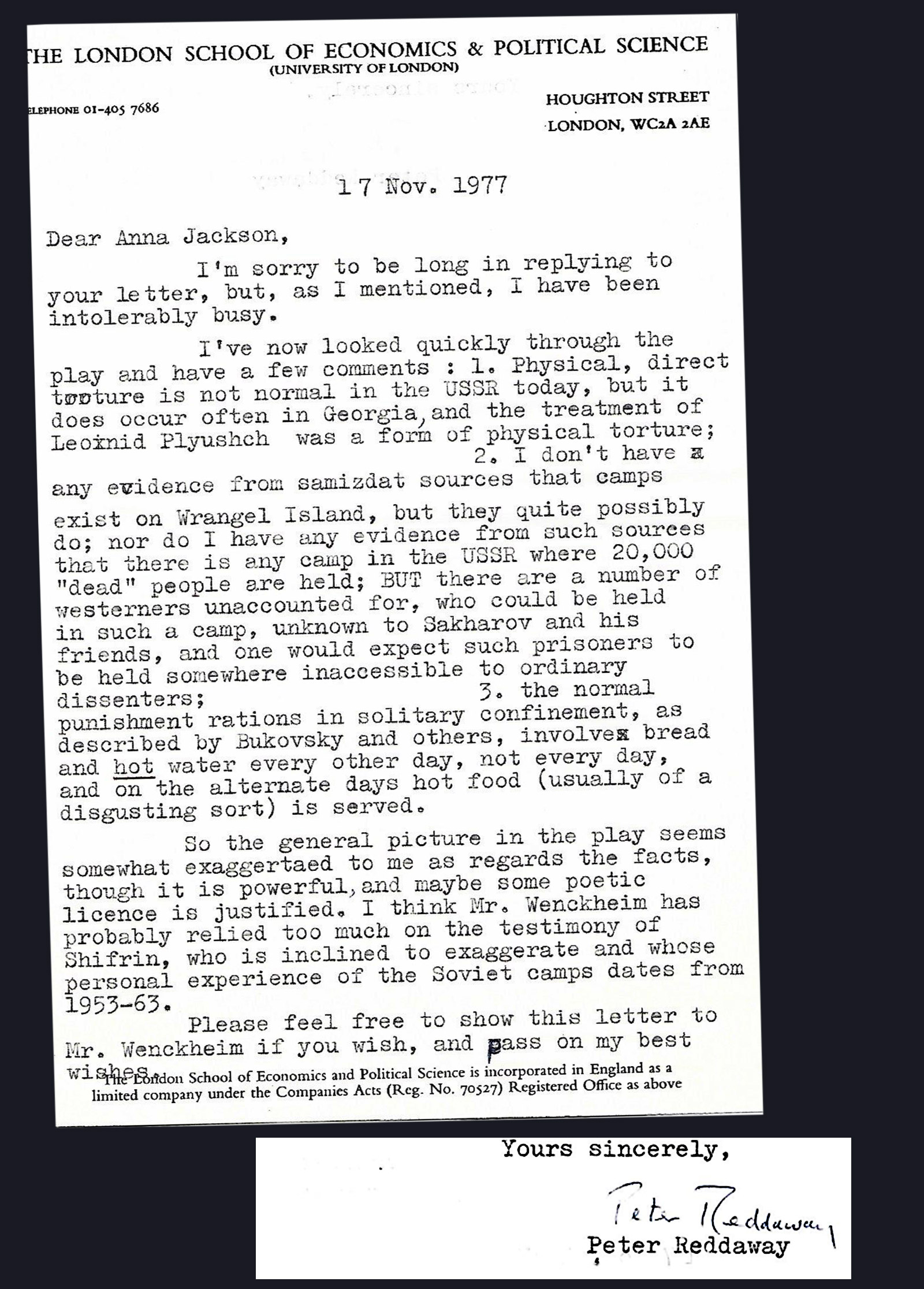

Who was learning, picking up hints, from whom? We went on trying to verify the allegations made in Wenckheim’s script.

The views of those who might know were inconclusive.

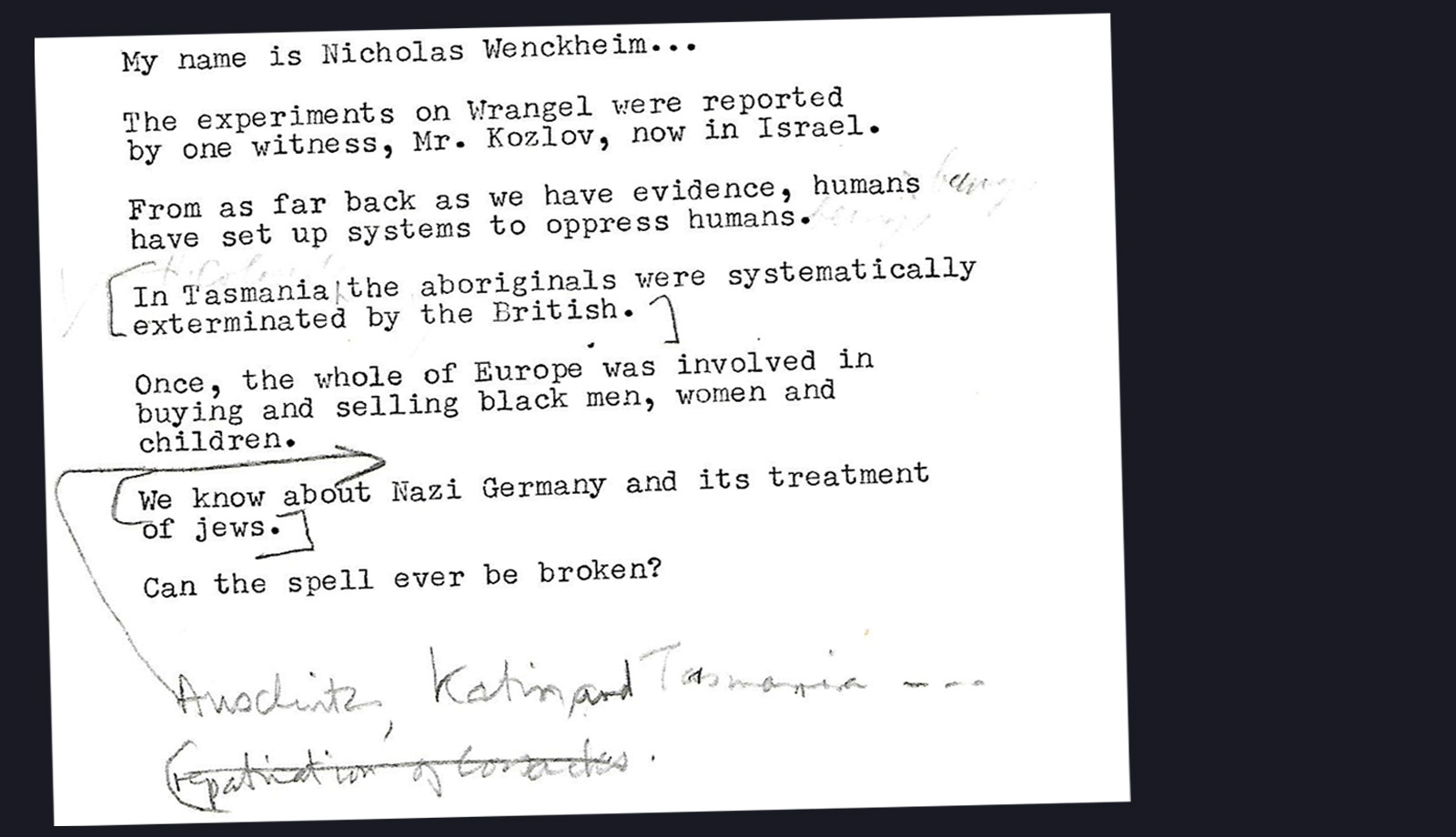

We even drafted a statement from Nicholas, thinking that if I directed Wrangel Island at the King’s Head it would serve as a disclaimer in the face of possible indignation and outrage from behind the Iron Curtain – and from Soviet sympathisers. To our quiet satisfaction we’d already discovered that controversy put bums on seats.

Pretty equivocal and wobbly, but perhaps worth a try. Being controversial, even shocking, on the London fringe was standard practice.

Then, we got this…

And I decided that the balance of the evidence for Soviet radiation experiments on live humans on Wrangel was negative. And that putting on this play would give the regime another retaliation point against the West for peddling false scare stories.

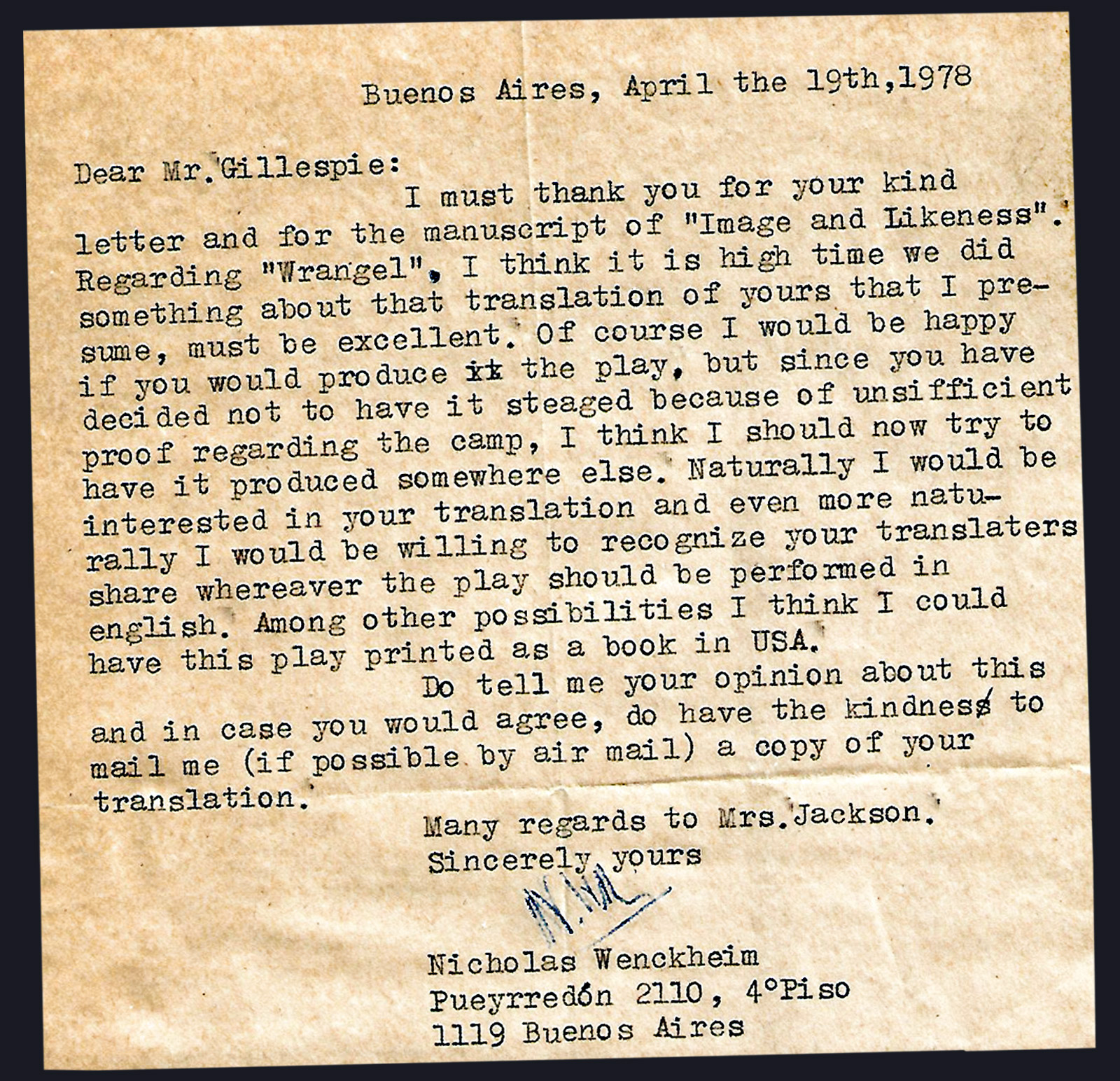

No longer to my surprise, Nicholas Wenckheim showed his resilience and tenacity. Also his unfailing, old-world, courtesy – with this…

I have a copy of The Ice Eaters. It’s a short, two-handed play. A mother is visiting her young son in a max security Soviet prison – he’s there for ‘accidentally’ sticking a pin into Lenin’s eye in a press photo on his first-ever day of work, when he was fifteen. When he’s nineteen, his mother is allowed a three-day visit. The horrors illustrated go beyond stock prison ill-treatment. There is a Spanish, a Goya-esque flavour to the tortures Wenckheim evokes. Also, a strong ‘spiritual’, a religious aura. Part of the son’s redemption is achieved through sacrificial incest; as if the ultimate offering of mother-love can overcome the worst that a secular, tyrannical state can do. It would be virtually impossible to place it now, but it’s the sort of play that could have been presented at the New Lindsey theatre in Notting Hill in the 50s and 60s as an ‘alternative’ to standard commercial theatre. It would have been sold as a Christian, a liberal-values based response to the materialistic horrors of the Soviet system; for a limited, but eager, public looking for something different.

The religious streak to Wenckheim soon became apparent, though I can’t remember if he told me he was a catholic. Also confirmed in another play of his; Kurti… (See Part Three)

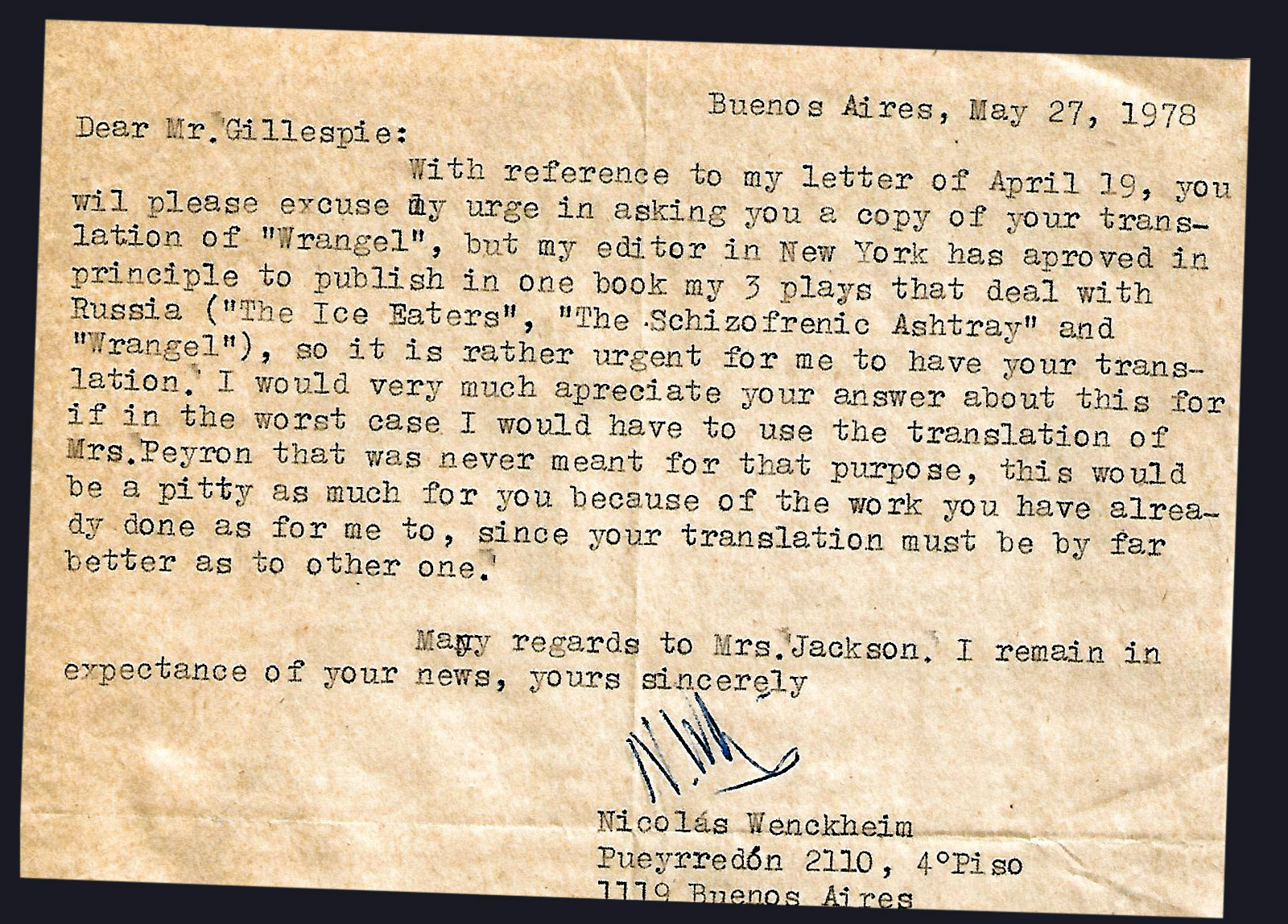

Also, his clout as a writer/translator was emerging. His talk of ‘my editor in New York’ was suitably impressive.

We could not help going on thinking about Wrangel Island. It was strong theatrical medicine.

End Part Five