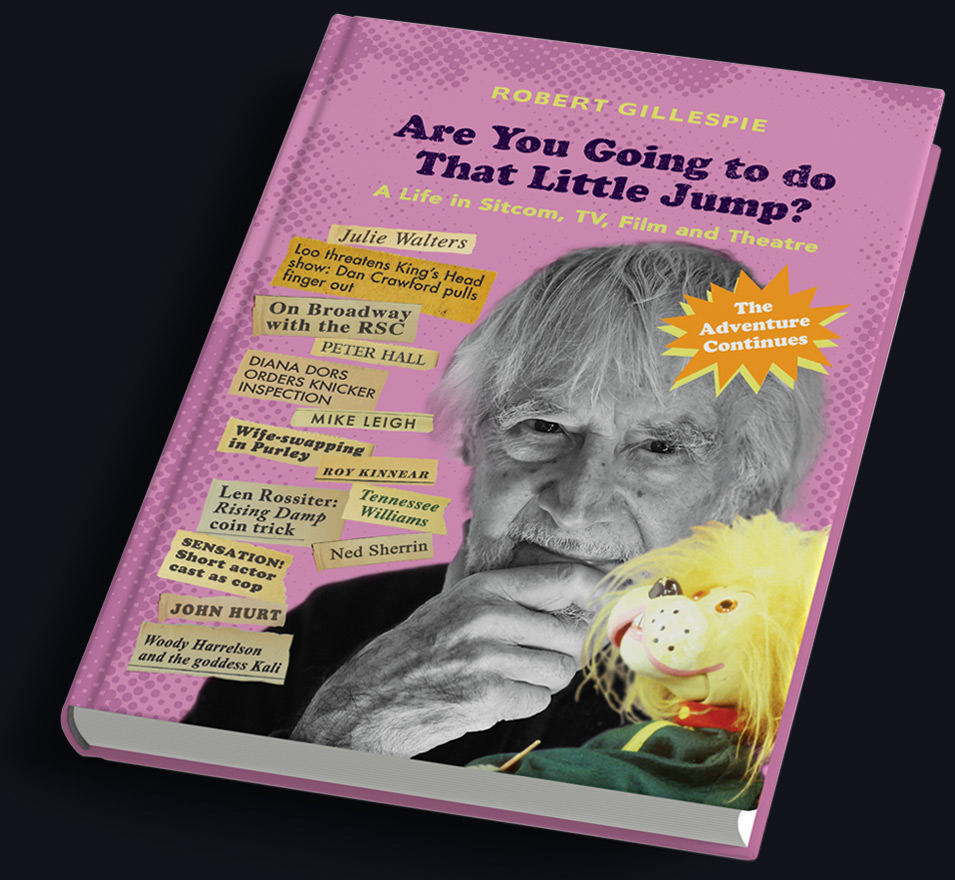

I first met Howard Goorney when we were both working with Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop in Stratford, east London. In Part One of Are You Going to do That Little Jump? I describe the weekly Soviet style meetings presided over by Joan. Though Howard was a long-term associate of hers, that didn’t stop him saying – after another six-hour session – ‘I don’t know why we bother with these meetings, Joan. You’re going to do what you want anyway; let’s just go home.’ Most of us believed Howard was a card-carrying Communist – but he was a nice Communist and he made us laugh.

I came across Howard again when I was up in Leeds, working for Yorkshire Television. We met, by chance, in a corridor between dressing rooms. He was very distressed.

‘Robert, I’m working on this kids’ show, it’s a beautiful show and we’re just about to record and the crew is striking. I can’t understand it; they’re extremely well paid; I fought for years to get them proper rates of pay.’ He was talking about his years of indefatigable union work. ‘They’re taking home a fortune, Robert, certainly compared with me or you, have you seen the cars they turn up in? And for a bit of extra cash they’re prepared to stop this recording. If we don’t do it now – it’s so expensive they’ll never get everything and everybody back again; it’ll be gone for good. What’s happened, Robert?’

He was close to tears. He paced the corridor agitatedly. Howard had a narrow, sensitive face and bushy hair, was rather a good actor, had a nice Jewish sense of humour and was normally unsentimental and slit-eyed about the world. It was striking to see him so shaken.

He was an honest Communist. I told him I held the view that the technicians had become a new exploiting class; as some miners had tried, for a while. It’s what I strove to explain to Kika Markham one time. When you are oppressed you come across as noble, downtrodden and deserving. When you climb up to take your turn in the driving seat, you exploit back. Nature of the beast.

Once, I experienced a blatant example of this working on Keep It In The Family. As I skipped from one studio set to the next, I could distinctly hear two blokes discussing union business behind one of our flats. It was happening in the middle of recording before a live audience. It affected the work.

It got to the point where Thames TV would only accept scripts with minimal filmed inserts because, by the 80s, they had to carry a minimum crew of twelve to film anything – someone taking in a bottle of milk! The BBC’s crewing had escalated to four! Now you can get away with one bloke with a digital device and integral sound. The ‘whirligig of time’ as your man has it.