The other time an actor threatened to unbalance a show I directed, by altering his character, could have been the most disastrous.

Jeremy Kingston, notable Punch and Times critic, had written an extremely witty and moving play, much in the manner of Noel Coward, which featured real historical figures – Noel himself, Lord Louis Mountbatten and Agatha Christie – when they were young. It is an historical fact that all three visited Burgh Island, off the coast of Devon – though not at the same time. Jeremy brought them together.

It is widely known, so I will not be doing him a dis-service, that Lord Louis was an extremely dominating royally connected posh chap, excessively full of himself with unshakable confidence in any and every idea he conjured up – of which there was an endless stream.

There is a scene in Jeremy’s play – it’s called Making Dickie Happy – in which a very young Mountbatten imposes himself on Agatha and offers her a brilliant plot for a detective story which he hasn’t time to write but believes she would do brilliantly. Christie is not used to being ordered what to write and very courteously declines. Lord Louis is furious.

It is generally believed to be a fact that the plot Mountbatten suggested was the core idea in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and that Christie, eventually, used it.

Now an indispensable strand in Jeremy’s play – much of the comedy – comes from young Lord Louis Mountbatten’s invincible arrogance and self-confidence.

He was celebrated for getting away with this because of his charm; which he knew he had and used, indeed weaponised.

Making Dickie Happy was so popular that we produced it at three different venues.

Two different actors were challenged with the opportunity to portray Mountbatten. The first, actor H, was entirely suited to the part, understood its function in the drama and relished the comic effect his splendid, comic arrogance wrought on the audience. There was huge laughter. But then… on a night when I was routinely seeing the play, I noticed the slightest, but disturbing softening in this actor’s delivery. The audience response was still there, but diluted.

I asked H whether he’d had just ‘one of those nights’ or whether he was changing his performance deliberately. ‘Well…’ and out it came. He’d begun to notice how often other people in the play described him as charming and had begun to wonder if he could be as potent in the part, even enhance its effect, if he went more for the dashing aspect and the irresistible and seductive charm of the character.

It doesn’t work, I said – and you’re in danger of destroying the immense comic pleasure of seeing a future young world leader throwing his weight about when he was a mere naval lieutenant. H looked a little doubtful, so I asked him if anyone had said anything to him, a friend – asked him if he needed to be quite so overweening and arrogant. H replied vaguely, inconclusively. Amber warning, to me. So I spent a few intense minutes describing, again, the ancient comic device of setting a reasonable, calm, logical person in hot debate with an impatient, over-confident, aggressive one – something H understood very well. It is as old as mankind itself. From that day on, H’s common sense, his professionalism and the history of enormous laughs that his scenes had been getting meant that he stuck to what he knew worked best.

The case of actor J was significantly different.

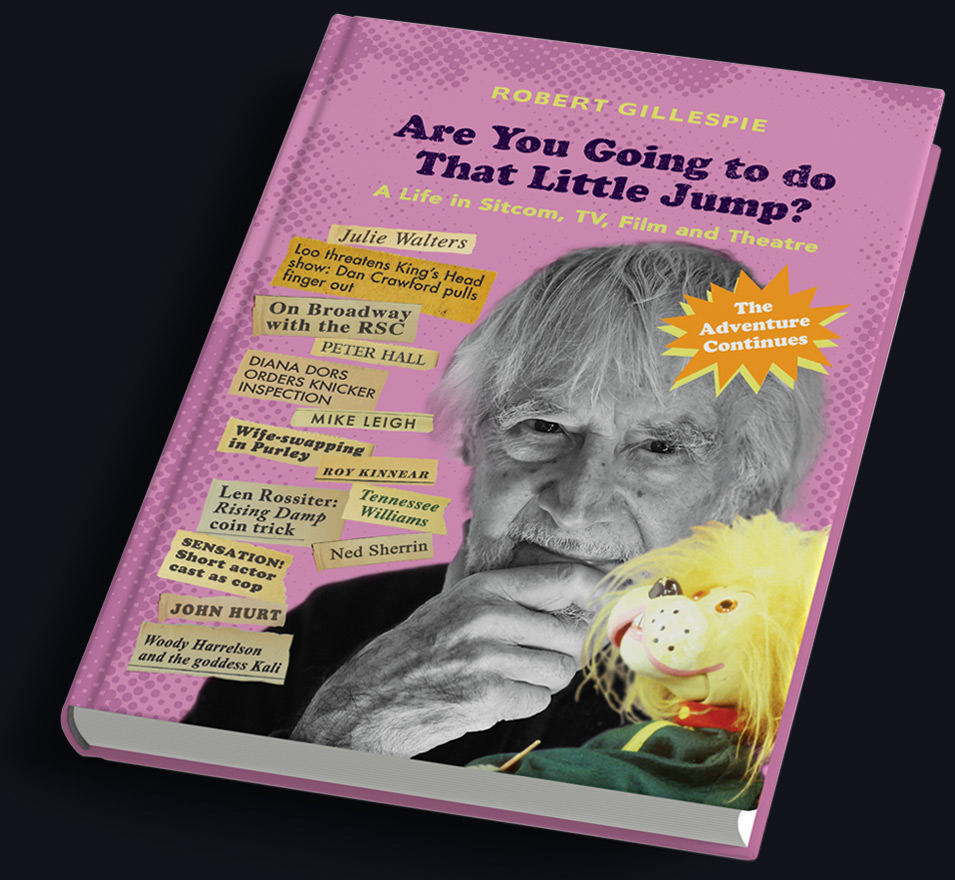

Readers of Part One of Are You Going to do That Little Jump? will know that, based on my own experience, I had a slit-eyed view of RADA. However, I’d recently seen a show at Southwark Playhouse put on by final RADA students and it was splendid. Performances and interpretation were of a very high standard and a complete contrast to the stuff I’d known when I was there – a long time back. So I approached the school and asked if they’d be interested in offering male students the chance to be in a revival of Making Dickie Happy at the Tristan Bates Theatre. I was, especially, looking for someone to play Dickie Mountbatten. Actor J read well and I cast him.

In J’s case the acting weather changed even during rehearsal. He would, one day, be sublime as the outrageous Dickie – the following day he’d wilt into a soppy softie just chucking in his lines on cue with bashful charm. I asked him what he thought he was doing. He said he believed rehearsal was a time for exploration – so as to be certain about where to pitch the final performance. O.K. But this rationalisation always sounds alarm bells for me – heard it before. Inevitably he, also, cited references made by other characters in the play to Dickie’s charm. Actors will rationalise interminably why they should be playing what they wish to play.

In the end, he had on nights and off nights in performance – didn’t quite wreck the show, but diminished it’s clout the nights he took the edge off his performance and played cuddly.

A complex individual, plausible, but I had a strong feeling that when he knew there was an agent in the house he made sure he wasn’t locked into the – to him – over-simple towering, dominant male persona of the essential Dickie. Intuition told me that he fancied himself, one day, as a fascinating, complex leading man heart-throb. RADA’s principal confided to me that he had his own question mark against J’s acting stats. Humans are far too complex to successfully interpret – but we all try. J didn’t trash the show, ever, but he made it unexpectedly uneven in its impact on the paying public.

Ends.